Osteochondroma is the most common benign bone tumor. The tumor is often diagnosed as an incidental finding. Osteochondromas account for approximately 35% of benign bone tumors and 9% of all bone tumors. Most are asymptomatic, but they can cause mechanical symptoms depending on their location and size.

As benign lesions, osteochondromas have no propensity for metastasis. In fewer than 1% of solitary osteochondromas, malignant degeneration of the cartilage cap into secondary chondrosarcoma has been described and is usually heralded by new onset of growth of the lesion, new onset of pain, or rapid growth of the lesion.[1, 2, 3]

NextHistorically and currently, most osteochondromas are incidental findings and are treated solely with observation. If they remain asymptomatic, they can be ignored. Lesions that create mechanical symptoms, become painful, begin to enlarge, or cause growth disturbance have historically been treated with surgical removal, and this remains the mainstay of treatment.

Osteochondroma is a benign, cartilaginous neoplasm that is found in any bone that undergoes enchondral bone formation in its development. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines osteochondroma as a cartilage-capped bony projection on the external surface of a bone. It is found most commonly around the knee and the proximal humerus; however, it can occur in any bone.

The osteochondroma may have a stalk and be defined as pedunculated (see the first and second images below), or it may have a broad base of attachment and be considered sessile (see the third image below). Whether the neoplasm is sessile or pedunculated, the medullary canal of the stalk and the bone are in continuity by definition.[4]

Solitary osteochondroma. Anteroposterior radiograph of a pedunculated osteochondroma of the distal femur.

Solitary osteochondroma. Anteroposterior radiograph of a pedunculated osteochondroma of the distal femur.

Solitary osteochondroma. Lateral radiograph of a pedunculated osteochondroma of the distal femur. Orientation is away from the growth plate, and medullary continuity is clear.

Solitary osteochondroma. Lateral radiograph of a pedunculated osteochondroma of the distal femur. Orientation is away from the growth plate, and medullary continuity is clear.

Solitary osteochondroma. Lateral radiograph of a sessile osteochondroma of the distal femur.

Solitary osteochondroma. Lateral radiograph of a sessile osteochondroma of the distal femur.

Osteochondroma is a hamartoma, and patients most commonly present in the second decade of life. Osteochondromas grow until skeletal maturity; growth generally stops once the growth plates fuse.[5] Slow growth from the cap may continue over time, as described by Virchow, but this usually stops by age 30 years.

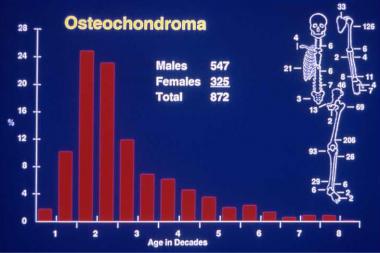

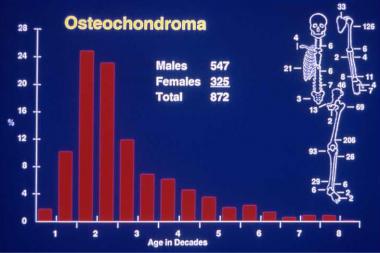

Osteochondromas are the most common benign bone tumors, representing 35% of all benign tumors and 9% of all bone tumors. However, their actual frequency is not known, because many osteochondromas are not diagnosed. Osteochondromas can occur in any bone that undergoes enchondral bone formation, but they are most common around the knee. Most are diagnosed in patients younger than 20 years (see the image below). A marked predilection for males exists; the male-to-female ratio is 3:1.[6]

Solitary osteochondroma. Anatomic and age distribution of solitary osteochondromas.

Solitary osteochondroma. Anatomic and age distribution of solitary osteochondromas.

Although the exact etiology of these growths is not known, a peripheral portion of the physis is thought to herniate from the growth plate.[7] This herniation may be idiopathic or may be the result of trauma or a perichondrial ring deficiency. Whatever the cause, the result is an abnormal extension of metaplastic cartilage that responds to the factors that stimulate the growth plate and thus results in exostosis growth.

This island of cartilage organizes into a structure similar to the epiphysis (see Workup, Histologic Findings, below). As this metaplastic cartilage is stimulated, enchondral bone formation occurs, developing a bony stalk. The histology of the cartilage cap reflects the classic, defined zones observed in the growth plate—namely, proliferation, columniation, hypertrophy, calcification, and ossification.

This theory is thought to explain the classic finding of the osteochondroma associated with a growth plate and growing away from the physis while maintaining its medullary continuity. The theory is also thought to explain the clinical behavior of the exostosis growing only until skeletal maturity.

Genetic karyotyping has suggested that reproducible genetic abnormalities are associated with these benign growths and that they may actually represent a true neoplastic process, not a reactive one.[8, 9] This research is in the early stages, and further investigation is necessary.[10, 11, 12, 13]

Heinritz et al reported on the clinical findings and results of molecular analyses of the EXT1 and EXT2 genes—mutations of which lead to multiple osteochondroma—in 23 patients. In 17 of the 23 patients, novel pathogenic mutations were identified (11 in the EXT1 gene; 6 in the EXT2 gene). According to the authors, findings of this study extend the mutational spectrum and understanding of the pathogenic effects of EXT1 and EXT2 mutations.[14]

Osteochondromas are located adjacent to growth plates and develop away from the growth plate with time because they are essentially isolated growth plates. They are affected by, and respond to, various growth factors and hormones in the same manner as epiphyseal growth plates do; thus, growth of an osteochondroma should cease at skeletal maturity.

Although osteochondromas can be located almost anywhere in the skeleton, almost half of them are found around the knee, in either the distal femur or the proximal tibia (see the image below).[15]

Solitary osteochondroma. Anatomic and age distribution of solitary osteochondromas.

Solitary osteochondroma. Anatomic and age distribution of solitary osteochondromas.

Osteochondromas are most commonly diagnosed incidentally on radiographs that were obtained for other reasons. The second most common presentation is a mass, which may or may not be associated with pain. Most of these lesions need not be treated, and asymptomatic lesions can be safely ignored. When painful, however, they must be evaluated properly.

Pain is usually caused by a direct mechanical mass effect of the osteochondroma on the overlying soft tissue. This can result in an associated sac or bursitis over the exostosis. Irritation of surrounding tendons, muscles, or nerves can result in pain.[16, 17] Pain can also result from fracture of the stalk of the osteochondroma from direct trauma. The bony cap of the stalk may infarct or undergo ischemic necrosis.

Asymptomatic lesions require no treatment and can be monitored initially with radiographs and subsequently by clinical examination. Further investigation is indicated if the patient presents with a painful lesion or develops pain or an increase in size of a preexisting lesion. Such changes may represent either a new mechanical symptom or malignant degeneration. MRI is very useful for investigating these changes. The most common causes of pain are bursa formation, impingement, fracture of the stalk, and malignant degeneration.[18, 19, 20]

Excision is the treatment of choice for symptomatic lesions. As with all lesions of muscle and bone, the physician must be confident of the diagnosis and well versed in the care of tumors, should the lesion in fact be malignant. If the surgeon has any doubt about the diagnosis of the lesion or the management of a potential malignancy, patient referral is the most appropriate course of action.

In excising the lesion, it is important to avoid leaving any remnants of cartilage from the cap or any perichondrium, because this can allow recurrence. The reported rate of local recurrence is less than 2-5%.[21, 22] The risk of recurrence is thought by some to be higher in the skeletally immature; therefore, resection might best be delayed until skeletal maturity is reached. Great care must be exercised with lesions close to the physeal plate in the immature patient, because of the risk of growth plate arrest and subsequent deformity.

Osteochondromas can occur in many different locations in the body. Thus, a complete understanding of local anatomy is paramount to ensure that local structures are not harmed during surgical resection. Because these lesions arise from the metaphysis, particular care must be taken to avoid damage to the growth plate in the skeletally immature patient.

No frank contraindications to removal exist, but the surgeon should be aware that a large osteochondroma may in fact be a chondrosarcoma and should exercise appropriate caution. Removal by a surgeon who is not well versed in dealing with orthopedic malignancies may be a relative contraindication.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved