Chordoma is a relatively rare malignant midline tumor arising in the axial skeleton, primarily at its cranial and caudal ends, that is derived from persistent embryonic notochordal cell rests.[1, 2, 3]

Shown below is an image demonstrating a lesion occurring in the vertebral column.

MRI scan demonstrates an osteolytic lesion involving the vertebral body. This lesion occurred in the mobile vertebral column.

MRI scan demonstrates an osteolytic lesion involving the vertebral body. This lesion occurred in the mobile vertebral column.

The notochord is derived from the primitive ectoderm and defines the midline of the chordate embryos. As the human fetus grows, the notochord expands at the site of the future intervertebral discs and forms the nucleus pulposus. The notochord regresses to leave an acellular sheath, except at its cephalic and caudal ends, where cell rests persist. Although this explains the observed distribution of chordomas (sphenoccipital and sacrococcygeal), it does not explain why the cell rests should transform into tumors.

A resemblance exists between notochordal and chordoma cells morphologically and immunohistochemically (positivity for S-100 protein, cytokeratin [CK], and epithelial membrane antigen [EMA]).[4, 5, 6]

Chordoma represents 1-4% of all primary bone tumors in various series. The incidence of chordomas is reported to be 8.4 cases per 10 million population. These tumors occur mostly in adults, with an overall peak distribution in patients aged 55-65 years. Rare cases in children and older individuals have been described. Chondroid chordomas affect slightly younger individuals, with a mean age of 40 years. Males are affected twice as frequently as are females, with 30-50% of cases in the sacrococcygeal location.

NextThese lesions present clinically as destructive bony masses with soft-tissue involvement. They erode and impinge upon adjacent structures, giving rise to a wide variety of clinical symptoms. In the cranial region, they can cause cranial nerve palsies, hydrocephalus, and torticollis (reported in an infant).[7] The sacral lesions can remain asymptomatic for a long time and/or present with a variety of nonspecific symptoms. These symptoms may involve back pain, changes in bowel habits, or a feeling of fullness in the rectal area. Physical examination must include a rectal examination to exclude a presacral mass.[8]

In children, the tumor may be more aggressive, with a variable histologic picture.

No specific blood tests exist for the diagnosis of chordoma. Routine investigations may be ordered in the workup, as indicated.

Plain radiographs

Sacrococcygeal chordomas present as midline lobular or geographic areas of radiolucency, occasionally expansile with an osteosclerotic rim. Skull-base chordomas present as radiolucent areas destroying the clivus and parasellar parts of the middle cranial fossa.[9]

CT scan

In addition to radiolucent foci, chordomas have an expansile concomitant soft-tissue mass, which is best visualized on CT scan. The soft-tissue masses frequently are calcified (50-70% of skull-base chordomas). They can protrude to present as nasopharyngeal masses (one third of cranial chordomas) or can compress the intestines and urinary bladder (sacrococcygeal chordomas).[9, 10]

MRI

MRI provides better delineation of the full extent of tumor due to its excellent contrast resolution capabilities (see image below) MRI also provides a better estimate of tumor volume compared with CT scanning. Both CT and MRI are vital for preoperative planning and staging of the disease.

Bone scans

Technetium-99m (99m Tc) bone scans demonstrate hot areas within the tumor. In the rare cases of chordoma observed in the mobile vertebral column (cervical, thoracic, lumbar), evidence of bony destruction and vertebral collapse is present. Frequently, 2 or more vertebrae are involved, showing destructive changes with a sclerotic rim. A paraspinal soft-tissue mass with calcification may be present.[10]

A fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or Tru-Cut needle biopsy may be obtained for diagnostic purposes. Both biopsies may require radiologic guidance, especially with skull-base tumors. With both types of biopsies, additional material should be obtained for ancillary studies.[11]

With FNAB, adequacy of material can be ascertained rapidly on site.[11] If indicated, during Tru-Cut needle biopsy, intraoperative cytology or a frozen section can be performed to determine whether appropriate tissue has been obtained. A definitive diagnosis usually is delayed until permanent analysis.

Careful preoperative planning is required before the biopsy is attempted. The biopsy should be the final diagnostic and/or staging procedure because it can distort radiologic imaging study findings, particularly MRI findings.

Based on light microscopic morphology, chordomas have been divided into 3 subtypes: conventional, chondroid, and dedifferentiated.

Conventional

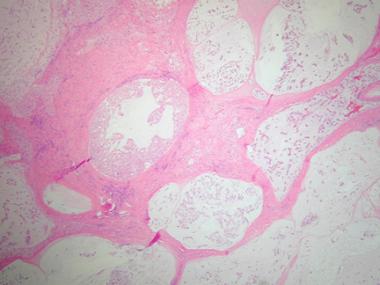

These are the most common type, are slow growing, and account for 1-4% of all malignant bone tumors. Grossly, conventional chordomas have a soft, tan, myxoid appearance with areas of hemorrhage. Microscopically, characteristic physaliphorous (from the Greek, meaning grapelike) cells are present, which are large with vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells are arranged in nests, cords, or sheets in a background of myxoid stroma as shown below.

Histologic section demonstrating lobular arrangement of tumor cells surrounded by fibrous connective tissue septa. Cellularity is variable with cells present in a pale myxoid matrix.

Histologic section demonstrating lobular arrangement of tumor cells surrounded by fibrous connective tissue septa. Cellularity is variable with cells present in a pale myxoid matrix.

Physaliphorous cells contain glycogen and mucin. Rarely, they can have a signet-ring appearance, with the cytoplasmic vacuole pushing the nucleus to the periphery. A second population of spindled stellate cells with no cytoplasmic mucin is also present. These are believed to be precursor cells. The myxoid stroma contains hyaluronidase-resistant sulfated mucopolysaccharides.

Chondroid

These are observed predominantly in the sphenoccipital location. They are slower growing than conventional chordomas and exhibit foci of chondroid (cartilaginous) differentiation adjacent to areas of conventional chordoma. In the chondroid areas, physaliphorous cells lie within lacunae surrounded by cartilaginous stroma. The tumors share ultrastructural features with chordoma, as well as cartilaginous tumors.

Some controversy exists regarding the histogenesis of these tumors. In a comparative light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of chordoma, chondroid chordoma, and chondrosarcoma involving the skull base, the immunohistochemical profile of chondrosarcoma was found to be different from that of the other 2 tumors (negative for CK, EMA, and carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA]). The authors concluded that chondroid chordoma is a variant of chordoma. Some authors have suggested using the term hyalinized chordoma to describe it, to clarify its histogenesis, and to avoid confusion with chondrosarcoma.[12]

Dedifferentiated

These are rapidly growing tumors with a poor prognosis. The tumors are biphasic, with areas of high-grade sarcoma that coexist alongside conventional or chondroid chordoma. The sarcomatous areas most commonly resemble malignant fibrous histiocytoma, although elements resembling fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and high-grade chondrosarcoma have been described. Most studies appear to suggest that they arise from sarcomatous transformation of chordoma, with some reporting their occurrence following postoperative radiotherapy for conventional chordoma.[13, 14, 15]

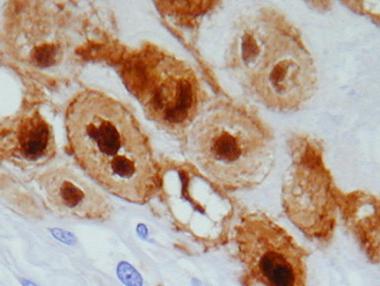

Immunohistochemically, physaliphorous cells in all types of chordoma are positive for S-100 protein (as depicted below), CK, and EMA. CEA also is positive in most cases.

S-100 immunostain of physaliphorous cells demonstrating strong nuclear staining.

S-100 immunostain of physaliphorous cells demonstrating strong nuclear staining.

In the anaplastic spindle cell areas of dedifferentiated chordoma, the epithelial markers CK and EMA usually are negative. In one report, although bordering areas between conventional and dedifferentiated chordoma exhibited EMA and CK positivity, EMA and CK were negative in the center of the sarcomatous areas. Vimentin and alpha1-antichymotrypsin were positive in these areas, which appears to support the pathogenesis of sarcomatous transformation from chordoma.[13, 14, 15, 16]

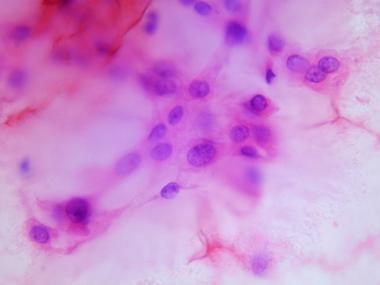

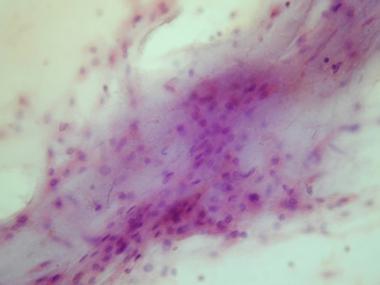

With the advent and development of FNAB cytology, FNAB is becoming a widely accepted technique for rapid, accurate, and economical diagnosis of a wide variety of lesions. In a study correlating cytologic findings in chordoma with histologic and radiologic features, commonly observed cytological features included typical physaliphorous cells (see top image shown below) and a second population of round-to-polygonal nonvacuolated epithelioid cells. The background had a myxoid or mucinous appearance (see bottom image shown below). In the dedifferentiated variety, physaliphorous cells were more pleomorphic, with nuclear inclusions, binucleation or multinucleation, and mitotic figures.[11]

Cytologic preparation demonstrating characteristic physaliphorous cells with bubbly cytoplasm at higher magnification.

Cytologic preparation demonstrating characteristic physaliphorous cells with bubbly cytoplasm at higher magnification.

Cytologic preparation demonstrating a sheet of low-grade polygonal large cells in a background of pale myxoid matrix.

Cytologic preparation demonstrating a sheet of low-grade polygonal large cells in a background of pale myxoid matrix.

Additional material should be obtained routinely for ancillary studies, especially immunocytochemistry. By FNAB cytology smears alone, chordoma has the potential to be confused with other conditions, such as metastatic adenocarcinoma. Depending on initial interpretation and differential diagnosis of FNAB cytology and core biopsy (frozen section), additional material can be obtained for other tests, such as electron microscopy and cytogenetic analysis.

No specific or characteristic anomalies are described in chordoma. However, cytogenetics is useful in distinguishing other lesions, such as myxoid chondrosarcoma [which has a specific t(9;22) translocation], from chordoma.

Conventional chondrosarcoma is an important differential diagnostic consideration for skull-base chordoma, especially chondroid chordoma. The location, which usually is off of the midline, and the immunohistochemical features (see Pathologic findings) can help distinguish between the 2 lesions.[5]

These lesions are likely to be confused with chordoma based on pathology. The histology of this lesion closely simulates that of chordoma. However, characteristic physaliphorous cells are not observed. Immunohistochemically, the cells are positive for S-100 and negative for CK and EMA. Clinically, these lesions arise in the extremities (mostly in soft tissue) and rarely involve the axial skeleton.

If a chordoma contains large numbers of cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles, it may be confused with metastatic adenocarcinoma.[17] However, metastatic adenocarcinoma usually lacks physaliphorous cells, and the extracellular mucin is of the neutral epithelial type, compared with the hyaluronidase-resistant sulfated mucopolysaccharide stroma of chordoma.

These tumors possess vacuolated lipoblasts, which may be mistaken for physaliphorous cells. However, they lack the lobular architecture and evenly distributed physaliphorous cells of chordoma. Further, the myxoid stroma in this tumor is hyaluronidase-sensitive nonsulfated mucopolysaccharide. Although both tumors are S-100 positive, myxoid liposarcoma lacks epithelial markers EMA and CK.

Polyvinylpyrrolidone is a high-molecular-weight hydrophilic substance that generally is used as a plasma substitute. Its high molecular weight prevents renal excretion and promotes accumulation within histiocytes, usually at injection sites within soft tissue. The histology of such soft-tissue mass lesions can resemble chordoma, as the bubbly, polyvinylpyrrolidone-laden histiocytes can simulate physaliphorous cells. They stain strongly with a variety of stains, such as Sudan black B and Congo red. The stroma usually lacks the myxoid character of chordoma. Location and the association with injection sites can help distinguish the lesions clinically.

Spinal Tumors

Careful staging is a prerequisite for appropriate management. Tumor extent and soft-tissue involvement are gauged by radiologic modalities. Biopsies are obtained to confirm the diagnosis. Chest radiography and CT scan of the chest can be obtained to detect pulmonary metastases. Technetium bone scan is useful to detect bone metastases.

Staging of lesions is based on imaging results and histopathologic and cytopathologic studies. The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system usually is used.[18] It is based on the following:

The definitions of the TNMG staging system are as follows:

Treatment options include low-dose or high-voltage radiation therapy, combined radiation and surgery, and surgical excision alone. It generally is accepted that complete surgical excision of the tumor is the only curative procedure. Due to local invasion, many tumors (especially skull-base chordomas) often are not amenable to complete surgical excision, and the local recurrence rate is high.[19, 20, 21, 22, 23]

Tumors detected and diagnosed early have a favorable prognosis if treated with a complete or en bloc excision.[24] A complete excision may involve a combined anterior-posterior operation, with anterior vertebrectomy, strut grafting, and possible stabilization with instrumentation. This is followed by a posterior decompression that also removes the pedicles and by stabilization of the spine with instrumentation above and below the excised levels.

Extension of the tumor beyond the confines of the vertebral body decreases the chances of a complete cure. Resection of the psoas muscle and sacrifice of lumbar or sacral nerve roots may be necessary. Preservation of both S3 nerve roots is required if normal bladder and bowel function are to be expected postoperatively. Surgical margin decisions in these cases are made on an individual basis. If complete resection of the tumor cannot be carried out and residual tumor is present either in bone or soft tissue, postoperative megavoltage radiation therapy is indicated.

Local recurrence rate is affected by tumor contamination of the surgical wound.[25] In one study, the recurrence rate was 64% when contamination was present and 28% when no contamination was present.[26]

The 5-year and 10-year survival rates for conventional chordoma are approximately 50% and 25-30%, respectively. Conversely, chondroid chordoma has 5-year and 10-year survival rates of approximately 80%. Survival rates appear to be influenced more by local tumor progression than by metastasis.[27, 9] A higher survival rate is associated with Hispanic race, smaller tumor size, and surgical intervention.

All 3 types of chordomas can metastasize, usually later in the course of the disease (except dedifferentiated chordomas, which can metastasize early). The usual metastatic sites are skin, bone, lung, and lymph nodes. Accurate prediction of metastatic potential is not possible, although certain clinical (local aggressiveness) and pathologic (anaplastic histology) features may be indicative. Vertebral body chordomas have a higher incidence of metastasis than do those arising in the clivus or sacrum.[28]

Some data suggest that female sex, tumor necrosis, and tumor volume of more than 70 mL are independent poor prognostic variables in skull-base chordomas. The difference in survival rate between the sexes suggests that hormone receptor status and hormone manipulation management may be areas for future investigation.[29]

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved