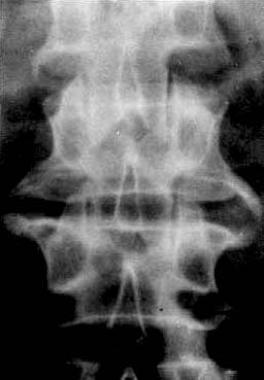

Lumbar spondylosis, as shown in the image below, describes bony overgrowths (osteophytes), predominantly those at the anterior, lateral, and, less commonly, posterior aspects of the superior and inferior margins of vertebral centra (bodies). This dynamic process increases with, and is perhaps an inevitable concomitant, of age.

Anteroposterior view of lumbar spine. Vertical overgrowths from margins of vertebral bodies represent osteophytes.

Anteroposterior view of lumbar spine. Vertical overgrowths from margins of vertebral bodies represent osteophytes.

Spondylosis deformans is responsible for the misconception that osteoarthritis was common in dinosaurs.[1] Osteoarthritis was rare, but spondylosis actually was common.

Lumbar spondylosis usually produces no symptoms. When back or sciatic pains are symptoms, lumbar spondylosis is usually an unrelated finding.

Past teleologically misleading names for this phenomenon are degenerative joint disease (it is not a joint), osteoarthritis (same critique), spondylitis (totally different disease), and hypertrophic arthritis (not an arthritis).

For further reading, please see the Medscape Reference article Lumbar Spondylosis and Spondylolysis.

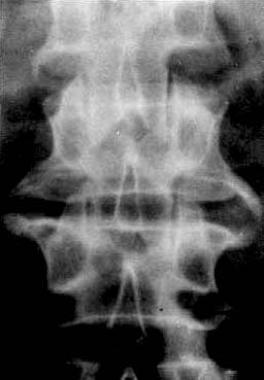

NextLumbar osteophytes, shown below, have long been thought to cause back pain because of their frequency and size, as depicted in the image below. This has led to many studies of the distribution of vertebral osteophytes, not all of which are pertinent. The frequency of signs or symptoms among individuals with osteophytes is no greater than among those individuals without osteophytes.[2]

Anteroposterior view of lumbar spine. Vertical overgrowths from margins of vertebral bodies represent osteophytes.

Anteroposterior view of lumbar spine. Vertical overgrowths from margins of vertebral bodies represent osteophytes.

Lumbar spondylosis is usually asymptomatic, with no diagnostic or prognostic significance.

Lumbar spondylosis is present in 27-37% of the asymptomatic population. In the United States, more than 80% of individuals older than 40 years have lumbar spondylosis, increasing from 3% of individuals aged 20-29 years.

Internationally, lumbar spondylosis can begin in persons as young as 20 years. It increases with, and perhaps is an inevitable concomitant of, age.

Approximately 84% of men and 74% of women have vertebral osteophytes, most frequently at T9-10 and L3 levels. Approximately 30% of men and 28% of women aged 55-64 years have lumbar osteophytes. Approximately 20% of men and 22% of women aged 45-64 years have lumbar osteophytes. Sex ratio reports have been variable but are essentially equal. Spinal osteophytosis in postmenopausal Japanese women correlated with the CC genotype of the transforming growth factor β1 gene.[3, 4]

Lumbar spondylosis occurs in animals with upright posture (eg, chimpanzees) and, possibly, in some domestic animals.[5]

Lumbar spondylosis appears to be a nonspecific aging phenomenon. Most studies suggest no relationship to lifestyle, height, weight, body mass, physical activity, cigarette and alcohol consumption, or reproductive history. Adiposity is seen as a risk factor in British populations, but not Japanese populations. The effects of heavy physical activity are controversial, as is a purported relationship to disk degeneration.[6]

Lumbar spondylosis occurs as a result of new bone formation in areas where the anular ligament is stressed.

Lumbar spondylosis usually produces no symptoms. When back or sciatic pains are symptoms, lumbar spondylosis is usually an unrelated finding. Lumbar spondylosis is usually not found unless a complication ensues.

Other problems to consider include the following:

Surgery is indicated only for complications (eg, for impingement-documented sciatica that is unresponsive to 2 days of absolute bed rest) of lumbar spondylosis.

The margins of vertebral bodies are normally smooth. Growth of new bone projecting horizontally at these margins identifies osteophytes. Most osteophytes are anterior or lateral in projection. Posterior vertebral osteophytes are less common and only rarely impinge upon the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Surgery is not indicated if no complications (eg, impingement) of lumbar spondylosis are present.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved