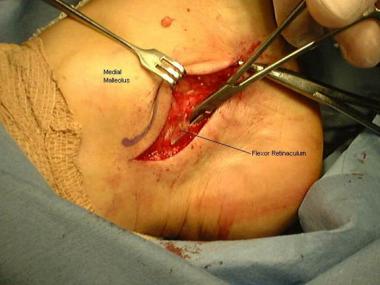

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a condition that is caused by compression of the tibial nerve or its associated branches as the nerve passes underneath the flexor retinaculum at the level of the ankle or distally.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] See the image below.

Surgical approach for release of the flexor retinaculum in a patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Surgical approach for release of the flexor retinaculum in a patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Gondring et al did a prospective evaluation of 46 consecutive patients (56 feet) who had nonoperative and surgical treatment for tarsal tunnel syndrome and documented pain intensity before and after treatment with the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale applied to the anatomic nerve regions of the plantar aspect of the foot.[9]

In the Gondring study, in patients who had successful nonoperative treatment, overall pain intensity was significantly improved in the medial calcaneal, medial plantar, and lateral plantar nerve regions. In patients who had ongoing symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, surgical treatment resulted in significant pain improvement in the medial calcaneal and medial plantar nerve regions, but not in the lateral plantar nerve area. Pretreatment motor nerve conduction latency was significantly greater in patients who had surgical treatment than in those who had only nonoperative treatment. The authors concluded that anatomic pain intensity rating models may be useful in the pretreatment and follow-up evaluation of tarsal tunnel syndrome.[9]

Antoniadas et al did a literature review of posterior tarsal tunnel syndrome and found that accurate diagnosis required proper clinical, neurologic, and neurophysiologic examinations. Success rates of 44-91% were attained with operative treatment. The results were found to be better in idiopathic cases than in posttraumatic cases, and if surgery failed, reoperation was indicated only in patients with inadequate release.[10]

NextTarsal tunnel syndrome is analogous to carpal tunnel syndrome of the wrist. In 1962, Keck and Lam first described the syndrome and its treatment.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a multifaceted compression neuropathy that typically manifests with pain and paresthesias that radiate from the medial ankle distally and, occasionally, proximally. These findings may have a variety of causes, which can be categorized as extrinsic, intrinsic, or tensioning factors in the development of signs and symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Extrinsic causes may contribute to the development of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Examples include external trauma due to crush injury, stretch injury, fractures, dislocations of the ankle and hindfoot, and severe ankle sprains.

Local causes may be intrinsic causes of the neuropathy. Examples include space-occupying masses, localized tumors, bony prominences, and a venous plexus within the tarsal canal.

Nerve tension caused by a valgus foot can cause symptoms that are identical to those of a circumferential nerve compression.

Symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome vary from individual to individual, but clinical findings generally include the following: sensory disturbance that varies from sharp pain to loss of sensation, motor disturbance with resultant atrophy of intrinsic musculature, and gait abnormality (eg, overpronation and a limp due to pain with weight bearing).

A hindfoot valgus deformity may potentiate the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome because the deformity may increase tension due to an increase in eversion and dorsiflexion.

To the authors' knowledge, no studies have demonstrated a statistical association for tarsal tunnel syndrome with work conditions or activities of daily living. The prevalence and incidence of tarsal tunnel syndrome have not been reported.

Several factors may contribute to the development of tarsal tunnel neuropathy. Soft-tissue masses may all contribute to compression neuropathy of the posterior tibial nerve. Examples of such masses include lipomas, tendon sheath ganglia, neoplasms within the tarsal canal, nerve sheath and nerve tumors, and varicose veins. Bony prominences and exostoses may also contribute to the disorder. A study by Daniels et al demonstrated that a valgus deformity of the rearfoot may contribute to the neuropathy by increasing the tensile load on the tibial nerve.[11]

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a compression neuropathy of the tibial nerve that is situated in the tarsal canal. The tarsal canal is formed by the flexor retinaculum, which extends posteriorly and distally to the medial malleolus.

The symptoms of compression and tension neuropathies are similar; therefore, differences in these conditions cannot be simply identified by the symptoms alone. In certain instances, compression and tension neuropathies may coexist.

The double-crush phenomenon originates from work published by Upton and McComas in 1973. The hypothesis behind this phenomenon may be stated as follows: Local damage to a nerve at one site along its course may sufficiently impair the overall functioning of the nerve cells (axonal flow), such that the nerve cells become more susceptible to compression trauma at distal sites than would normally be the case.

The nerves are responsible for transmitting afferent and efferent signals along their length, and they are also responsible for moving their own nutrients, which are essential for optimal functioning. The movement of these intracellular nutrients is accomplished through a type of cytoplasm within the nerve cell called axoplasm (referring to cytoplasm of the axon). The axoplasm moves freely along the entire length of the nerve. If the flow of the axoplasm (ie, axoplasmic flow) is blocked, the nerve tissue that is distal to that site of compression is nutritionally deprived and more susceptible to injury.[12]

Upton and McComas further suggested that a high proportion (75%) of patients with one peripheral nerve lesion did, in fact, have a second lesion elsewhere. The authors implied that both lesions contribute to the patients' symptoms. These lesions were originally studied in cases of brachial plexus injury with an increased incidence of carpal tunnel neuropathy. An analogous example of the double-crush phenomenon in the feet would be a compression of the S1 nerve root, resulting in an increased likelihood of compression neuropathy in the tarsal canal.

Clinical assessment of the patient with suspected peripheral neuropathy should include careful review of the past medical history, with attention to systemic diseases that can be associated with peripheral neuropathy, such as diabetes and hypothyroidism.

Many medications can also cause a peripheral neuropathy. These include nitrous oxide, colchicine, metronidazole, lithium, phenytoin, cimetidine, disulfiram, chloroquine, amitriptyline, thalidomide, cisplatin, pyridoxine, and paclitaxel. Conditions that are related to these drugs typically involve distal symmetric sensorimotor neuropathy. Any patient drug or alcohol use or exposure to solvents and heavy metals should be investigated.

Patients should also be questioned about their exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), vitamin use, Lyme disease, and foreign travel (ie, exposure to leprosy). A family history that demonstrates the familial presence of hammer toes, cavus foot, gait abnormalities, and muscle weakness may indicate a long-standing or familial neuropathy.

Patients typically present with vague symptoms of foot pain, which can sometimes be confused with plantar fasciitis. Findings of pain, paresthesias, and numbness are not uncommon. In some cases, atrophy of the intrinsic foot muscles may be noted, although this may be clinically difficult to ascertain. Eversion and dorsiflexion may cause symptoms to increase at the endpoint range of motion.

The Tinel sign (radiation of pain and paresthesias along the course of the nerve) may often be induced posterior to the medial malleolus. Symptoms generally subside with rest, although they typically do not disappear altogether. (Percussion of a nerve with a resultant distal manifestation of paresthesias is known as the Tinel sign. This should not be confused with the Phalen sign, which is compression of the suspected nerve for 30 seconds, with subsequent reproduction of the patient's symptoms.)

Physical examination may demonstrate reduced sensitivity to light touch, pinprick, and temperature in patients with distal symmetric sensorimotor neuropathy.

Radiographic examination of the patient's limbs may demonstrate loss of bone density, thinning of the phalanges, or evidence of neuroarthropathy (eg, Charcot disease) in long-standing neuropathies. Additionally, trophic changes may include pes cavus, loss of hair, and ulceration. These findings are most prominent in those with diabetes, amyloid neuropathy, leprosy, or hereditary motor sensory neuropathy (HMSN) with prominent sensory involvement. Perineural thickening may be noted in cases of leprosy and amyloid neuropathy.

A positive history combined with supportive physical findings (see Clinical, Physical examination) and positive electrodiagnostic results makes the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel neuropathy highly likely. Patients with a high likelihood of nerve compression generally have a good clinical result after surgical decompression of the tibial nerve. It is important to note, however, that the absence of positive electrodiagnostic results does not rule out the possibility of decompression for treating the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

The tarsal tunnel is a structure in the foot that is formed between the underlying bones of the foot and the overlying fibrous tissue. The flexor retinaculum (laciniate ligament) constitutes the roof of the tarsal tunnel and is formed by the deep fascia of the leg and the deep transverse fascia of the ankle. The proximal and inferior borders of the tunnel are formed by the inferior and superior margins of the flexor retinaculum. The floor of the tunnel is formed by the superior aspect of the calcaneus, the medial wall of the talus, and the distal-medial aspect of the tibia. The remaining fibroosseous canal forms the tibiocalcaneal tunnel. The tendons of the flexor hallucis longus muscle, flexor digitorum longus muscle, tibialis posterior muscle, posterior tibial nerve, and posterior tibial artery pass through the tarsal tunnel.

The posterior tibial nerve lies between the posterior tibial muscle and the flexor digitorum longus muscle in the proximal region of the leg and then passes between the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus muscle in the distal region of the leg. The tibial nerve passes behind the medial malleolus and through the tarsal tunnel and then bifurcates into cutaneous, articular, and vascular branches. The main divisions of the posterior tibial nerve include the calcaneal, medial plantar, and lateral plantar nerve branches. The medial plantar nerve passes superior to the abductor hallucis and flexor hallucis longus muscles and later divides into the 3 medial common digital nerves of the foot and the medial plantar cutaneous nerve of the hallux. The lateral plantar nerve travels directly through the belly of the abductor hallucis muscle, where it later subdivides into branches.

The innervation of the branches of the posterior tibial nerve is as follows:

Surgery is contraindicated in patients who are not medically stable enough to undergo this elective procedure. In addition, appropriate medical workup should be initiated in patients who may have medical comorbidities that may preclude them from undergoing such procedures.

Several conditions may mimic or coexist with tarsal tunnel neuropathy. Surgical treatment may depend on an accurate determination of the conditions that are similar to tarsal tunnel syndrome but do not improve after surgical decompression.

The differential diagnosis for tarsal tunnel syndrome may include plantar fasciitis; stress fractures of the hindfoot, particularly the calcaneus; herniated spinal disk; peripheral neuropathies, such as those caused by diabetes or alcoholism; and inflammatory arthritides, such as Reiter syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved