Fibular development and its impact on the kinematics of the ankle and foot are complex topics.[1, 2, 3] The normal fibula is approximately equal in length to the tibia, but its distal tip extends more caudad. Thus, the fibula acts as a lateral buttress, bearing approximately 15% of the body weight during gait. Ankle valgus is an insidious deformity that results in pronation of the foot and medial malleolar prominence. The causes are varied and include neuromuscular disorders, skeletal dysplasia, and clubfoot.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

Left untreated, this deformity may progress, despite the use of orthotics or corrective shoes, resulting in the medial collapse of the ankle and foot. After skeletal maturity, the only remedy is to perform a supramalleolar osteotomy. However, in growing children, there is the opportunity to intervene by means of guided growth or hemiepiphysiodesis of the distal medial tibia.

This article focuses on discussing the pathophysiology and evolution of ankle valgus and elucidating the role of guided growth (prior to skeletal maturity) to reverse this problem, without the need for osteotomy. If the physis has closed, an osteotomy will be required.

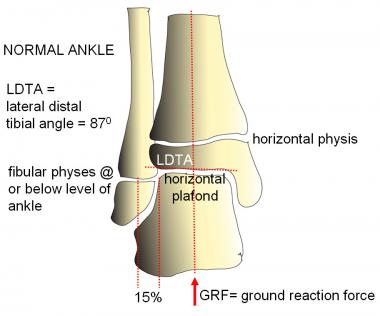

NextNormal ankle anatomy (see the image below) has the following characteristics:

Normal ankle alignment. The lateral distal tibial angle (LDTA) is 87º, and the fibular physis is at or distal to the level of the plafond, which is horizontal and, thus, perpendicular to gravity.

Normal ankle alignment. The lateral distal tibial angle (LDTA) is 87º, and the fibular physis is at or distal to the level of the plafond, which is horizontal and, thus, perpendicular to gravity.

Ankle valgus has the following characteristics:

In the normally aligned extremity, the mechanical axis bisects the knee and ankle, at an angle of 3º with respect to the vertical (gravity). The tip of the fibula is caudad to the medial malleolus, and the fibula serves as a lateral buttress to the ankle, bearing up to 15% of the weight. This preserves a horizontal plafond and ameliorates strain on the deltoid and tibiofibular ligaments.The alignment of the tibial and fibular physes, along with the ankle plafond, parallel to the floor and perpendicular to gravity permits the physeal and articular cartilage chondrocytes to resist compression—a task for which they are well suited—while sparing them from shear forces.

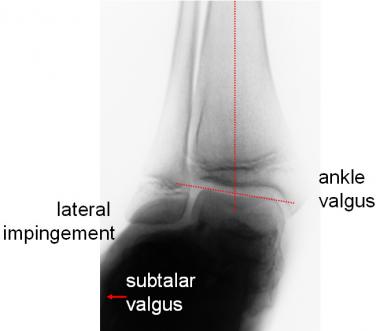

If the fibula is foreshortened because of developmental, posttraumatic, or iatrogenic causes, the lateral buttress effect is lost. As the ankle tilts and the ground reaction force shifts laterally, the balance changes. The deltoid and interosseous ligaments are subject to strain, and the lateral distal tibial epiphysis is compressed, resulting in characteristic wedging. The distal fibular epiphysis may enlarge, reflecting the Heuter-Volkmann principle as it impinges on the hindfoot and assumes increased weightbearing stresses (see the image below).

Lateral impingement may be due to ankle valgus, hindfoot valgus, or both. This is an extreme example.

Lateral impingement may be due to ankle valgus, hindfoot valgus, or both. This is an extreme example.

This process continues in a vicious circle that is refractory to shoe modification or bracing; eventually, surgical intervention is needed. Ankle valgus may also contribute to progressive outward rotation of the tibia and result in secondary valgus strain on the knee.

The severity and progression of ankle valgus may be assessed on the basis of the Malhotra grading system (see Workup).

Ankle valgus, which is rare at birth, may gradually develop because of a variety of conditions, including (but not limited to) the following[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] :

In a retrospective study by Burghardt et al, ankle valgus was found to have developed postoperatively in 55.8% of feet in a group of pediatric patients who had undergone surgery for idiopathic clubfoot.[14]

All told, ankle valgus is considerably more common than (bony) ankle varus. Often bilateral, it may be seen in conjunction with other limb malalignment problems, including subtalar valgus (or varus) and genu valgum. When unilateral, it may contribute to relative foreshortening of the limb as a consequence of lateral tilt and translocation of the hindfoot. This will not be appreciated on a scanogram; a standing anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the ankles is necessary to document its contribution.[15, 16]

Depending on the etiology, ankle valgus is often bilateral; its overall frequency is unknown. It is far more common than ankle varus and may accompany (or mimic) hindfoot deformities, compounding their management. Developing during childhood, if left untreated, it may become relatively disabling by the time of skeletal maturity.

As ankle valgus corrects, bracing is facilitated or, in some cases, obviated, and shoewear improves. Lateral impingement and subfibular pain are ameliorated.

Compared to the knee, where rapid improvement is noted, the ankle grows slowly. This is especially true in patients with neuromuscular compromise or skeletal dysplasias. Nevertheless, over the course of 18-24 months, most children will manifest signs of clinical and radiographic improvement. The flexible extraphyseal implant may be left in situ longer, if necessary. The theoretical risk of physeal closure is progressive ankle varus (not encountered to date); this may be remedied with an opening wedge supramalleolar osteotomy.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved