The term scoliosis is derived from the Greek word skolios ("twisted") and refers to a sideward (right or left) curve in the spine. Scoliosis is not a simple curve to one side but, in fact, is a more complex, 3-dimensional deformity that often develops in childhood. See images below.

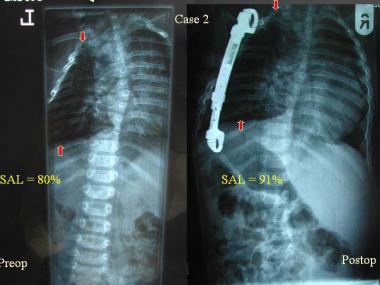

Preoperative and postoperative radiographs show an increase in the space available for lung (SAL) after correction of scoliosis by VEPTR (vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib).

Preoperative and postoperative radiographs show an increase in the space available for lung (SAL) after correction of scoliosis by VEPTR (vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib).

Preoperative and postoperative radiographs show an increase in the space available for lung (SAL) after correction of scoliosis by VEPTR (vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib).

Preoperative and postoperative radiographs show an increase in the space available for lung (SAL) after correction of scoliosis by VEPTR (vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib).

In a retrospective study of the treatment of patients with idiopathic infantile scoliosis, 31 consecutive patients (average age, 25 mo) with a primary diagnosis of idiopathic infantile scoliosis were reviewed. Treatment modalities included bracing, serial body casting, and vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR). Of the 31 patients, 17 were treated with a brace, 9 of whom had curve progression and subsequently received other treatments. Of the 8 patients who responded to brace treatment, overall improvement was 51.2%. Patients who received body casts had a mean preoperative Cobb angle of 50.4º and had an average correction of 59.0%. Patients who were treated with VEPTR had a mean preoperative Cobb angle of 90º and had an average correction of 33.8%. The study results suggest that body casting is useful in cases of smaller, flexible spinal curves, and VEPTR is a viable alternative for larger curves.[1] Another study concluded that brace treatment can be successful.[2]

Another retrospective case series, of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in patients with presumed infantile idiopathic scoliosis, reviewed the medical records of 54 patients. MRI revealed a neural axis abnormality in 7 (13%) of 54 patients who underwent MRI. Of these 7 patients, 5 (71.4%) required neurosurgical intervention. Tethered cord requiring surgical release was identified in 3 patients, Chiari malformation requiring surgical decompression was found in 2 patients, and a small nonoperative syrinx was found in 2 patients. The authors concluded that on the basis of these findings, close observation may be a reasonable alternative to an immediate screening MRI in patients presenting with presumed infantile idiopathic scoliosis and a curve greater than 20º.[3]

A recent study reviewed the frequency of asymmetric lung perfusion and ventilation in children with congenital or infantile thoracic scoliosis before surgical treatment and the relationship between Cobb angle and asymmetry of lung function. The authors found that asymmetric ventilation and perfusion between the right and left lungs occurred in more than half of the children with severe congenital and infantile thoracic scoliosis, but the severity of lung function asymmetry did not relate to Cobb angle measurements. Asymmetry in lung function was influenced by deformity of the chest wall in multiple dimensions and could not be ascertained by chest radiographs alone.[4]

NextProbably the oldest mention of scoliosis is in ancient Hindu mythology (3500 to 1800 BC), in which Krishna corrects the hunchback of one of his followers. Hippocrates (460 to 377 BC) wrote about scoliosis and devices to correct it. The term infantile scoliosis was first used by Harrenstein in 1930 and by James in 1951 in describing the clinical entity idiopathic infantile scoliosis.[5, 6, 7]

The term infantile scoliosis is used specifically to describe scoliosis that occurs in children younger than 3 years. Other terms for scoliosis also depend on the age of onset, such as juvenile scoliosis, which occurs in children aged 4-9 years, and adolescent scoliosis, which occurs in those aged 10-18 years. These terms, however, are now being replaced by the broader terms early-onset scoliosis and late-onset scoliosis, depending on whether the scoliosis occurs before or after 5 years of age.

In 80% of cases of scoliosis, there is no obvious cause; this is termed idiopathic scoliosis. In the remaining 20% of cases, a definite cause can be found. These cases are divided into 2 types: nonstructural (functional) and structural scoliosis, which could be part of a well-recognized syndrome (syndromic scoliosis), congenital spinal column abnormalities (congenital scoliosis), neurologic disorders, and genetic conditions.

Recent evidence in the literature from 2 major centers in the United Kingdom suggests the association of neural axis anomalies with early-onset idiopathic scoliosis is only 11.1%.

The syndromes that can produce congenital scoliosis are VATER syndrome (vertebral anomalies, anorectal anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula, and renal anomalies), VACTERL syndrome (vertebral anomalies, anorectal anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal and vascular anomalies, and cardiac and limb defects), Jarcho-Levin syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome, Alagille syndrome, Wildervank syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and MURCS association (Müllerian, renal, cervicothoracic, and somite abnormalities).

The congenital anomalies of the vertebral spinal column include defects of segmentation (block vertebra, unilateral bar) and defects of formation (hemivertebra — fully segmented, semisegmented, incarcerated and nonsegmented, wedge vertebra). The neurologic deficits in congenital scoliosis may be secondary to the spinal deformity or may be associated with vertebral anomalies (spinal dysraphism — diastematomyelia, myelocele, myelomeningocele, meningocele). A higher incidence of idiopathic scoliosis has been reported in families of children with congenital scoliosis. Spondylocostal dysostosis (Jarcho-Levin syndrome) has a genetic etiology.[8, 9, 10, 11]

Infantile scoliosis is a rare condition, accounting for less than 1% of cases of idiopathic scoliosis in North America; in Europe, the rate is 4%.

Sex: Males account for 60% of the cases of early-onset scoliosis; 90% of the cases of early-onset scoliosis resolve spontaneously, but the other 10% of cases progress to a severe and disabling condition. Females constitute 90% of late-onset cases and need close monitoring to intervene at appropriate times.

Although the exact cause of idiopathic infantile scoliosis is not known, hypotheses have been proposed on the basis of epidemiologic evidence[8, 9, 10, 12, 13] :

Most of the curves in the spine develop during the first year of life, and strong correlation has been found between the nursing posture of the infant and development of the curve. It is less common in the United States than in Europe, where babies are nursed in the supine position. Infants have a natural tendency to turn toward the right side, and because of plasticity of the infant's axial skeleton, this can lead to development of plagiocephaly, bat ear on the right side, and curvature of the spine toward the left side.[12]

Infantile scoliosis usually is detected during the first year of life either by the parents or by the pediatrician during routine examination of the infant. Usually, a single, long, thoracic curve to the left is present; less often, a thoracic and lumbar double curve is noted. A child who is diagnosed with scoliosis requires a thorough clinical and radiologic examination to exclude any congenital, muscular, or neurologic causes.

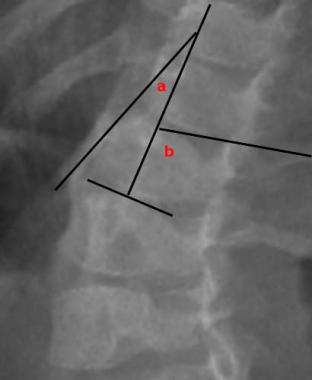

There are 3 management options for infantile scoliosis: observation, orthosis, and operative.[14] The decision when to use each of these is based on the rib-vertebral angle difference (RVAD), established by Mehta in 1972, as seen in the image below.[15] The RVAD is a useful guide in distinguishing between resolving and progressive idiopathic infantile scoliosis.

RVAD (rib-vertebral angle difference) measurement at apical vertebra: RVAD = b-a (concave - convex side).

RVAD (rib-vertebral angle difference) measurement at apical vertebra: RVAD = b-a (concave - convex side).

The rib-vertebrae angle is measured by (1) drawing a line perpendicular to the middle of the upper or lower border of the apical vertebrae of the curve and then (2) measuring the angle this line makes with medial extension of another line drawn from the mid point of the head to the mid point of the neck of the rib, just medial to the beginning of the shaft of the rib. The difference between the right and the left side (concave and the convex side) is the RVAD.

The apical vertebra is the vertebra at the curve of the apex. If there are the same number of vertebrae between the superior and the inferior end vertebrae, there will be 2 apical vertebrae.

For scoliosis curves with an RVAD of less than 20°, observation every 4-6 months is sufficient. If the RVAD is more than 20° or if it is not flexible clinically (ie, curve cannot be corrected even slightly with different postures, especially lateral bending), then it is considered to be progressive until proven otherwise.

Normally, there are interobserver and intraobserver variations with these radiographic parameters. Corona et al in 2012 found that even though variations are present in the radiographic parameters of RVAD, Cobb angle, and the space available for lung (SAL), these radiographic parameters are useful tools for planning management options. According to the authors, even though these parameters are not devoid of variability, they are not skewed enough and that the RVAD and the Cobb angle are highly reliable to accurately and reliably suggest the best course of treatment.

Management with orthosis is necessary when the curve is considered to be progressive or if a compensatory curve has developed.[16] Various types of orthosis are available for children younger than 3 years. The most commonly used orthoses are the hinged Risser jacket; the plaster spinal jacket (Cotrel EDF [elongation, derotation, flexion] type) applied under anesthesia; the Milwaukee brace; and the Boston brace. The brace should be used for 23.5 hours a day and should be removed only for exercises and swimming. It needs to be used until skeletal maturity is attained, because curves usually do not progress after skeletal maturity; however, curves may progress in spite of using a brace.[17, 18]

Spinal deformity in scoliosis progresses during periods of peak growth velocity. The first spinal growth peak occurs at 2 years of age, and the second peak occurs during the prepubescent period.

Operation is usually an option only for children in older age groups (ie, around age 10 years), and segmental posterior wiring to 2 L-rods without fusion is preferable until combined posterior and anterior fusion can be done. These procedures, however, have been associated with complications in 50% of patients.

Because of advances in instrumentation, pedicle screw instrumentation can be performed for children with further growth potential.[19] In these patients, a growing rod is used, which is associated with fewer complications than surgical fixation using L-rods. The disadvantage associated with the growing rod is that every 6 months the posterior aspect has to be opened to lengthen the rod, which increases the risk of infection; however, if the curve is severe or increases despite the use of orthosis, a short anterior and posterior fusion is recommended to prevent crankshaft phenomenon.

The spine is made up of 33 individual vertebrae that form a column. The spine is divided into 5 regions, starting from the top:

The sacrum and coccyx are fused in the adult. The spine provides a protective function for the spinal cord; bears and distributes the weight of the body; provides an area for attachment of ligaments and muscles; and is the site for production of red blood cells. Together, all the vertebrae form a flexible structure providing mobility for the body to bend forward or sideward.

Each vertebra has a cushionlike fibrous structure called a disk, which acts like a shock absorber during movements of the spine. The disk is made up of a soft, jellylike central nucleus pulposus surrounded by a ring of fibrous tissue called an anulus, which is actually a strong ligament between 2 adjacent vertebrae.

Developmentally, the spine of the fetus is C-shaped, with concavity in the front (kyphotic) of the thoracic region; this is called the primary curve. Two secondary curves develop after birth, with concavity occurring anteriorly (lordosis); one of the secondary curves develops in the cervical region as the infant starts to hold up the neck, and the second curve develops in the lumbar region when the child starts to walk. Normally, there are no sideward (scoliosis) curves, so that the spine looks straight when viewed from behind or from the front.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved